Back in 1992, I borrowed a DDS tape drive from my day job to back up all of my Macintosh hard drives at home. I stored the tape in a safe deposit box, until years later when it was relegated to the bottom of a storage box in the basement. Upon reviving my interest in Macs about five years ago, I encountered the tape. Given that I never owned a DDS drive and I hadn't documented which backup software I had used, I set the tape aside assuming I could never restore it. Every time I visited my basement boxes, the tape haunted me.

Recently, while looking for something else in my old utilities collection, I ran into a folder containing Retrospect 1.3B, circa 1991/1992. That was enough to warrant trying to restore the tape. I ordered a Sony SDT-7000 in an external SCSI case from eBay, along with some new-old-stock tapes for practice.

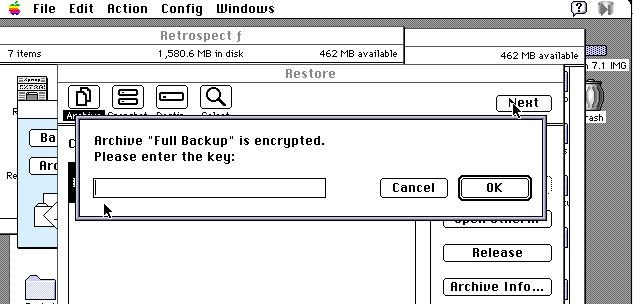

I first used the practice tapes to determine that the tape drive was functioning and was not going to eat my backup. Then, after inserting my real backup tape, I was greeted with the following dialog:

Oh no! What password did I use 33 years ago?

After trying the usual passwords, I decided to crack the software. I've done this on many other programs from that era. Usually, they do a simple comparison against a plain-text stored copy of the password, or better ones compare it to a hash. Simply replacing the fail condition with a NOP or changing the success branch to an unconditional BRA is enough to crack the program. For example, this technique works with HDT drivers because they don't want to incur the speed penalty of encrypting/decrypting the hard drive sectors.

Here are the steps to take:

1. Make sure the debugger, MacsBug, is installed

2. On the password request screen, press the interrupt button on the Mac to drop into MacsBug.

3. Type SC6 to get a list of the routines on the stack. Usually, the last several will be in the operating system. You're looking for application routines, which are usually marked 'CODE xxxxx' because they come from the program's 'CODE' resource.

0128AD82 01275E50 'CODE 0009 1B2E Arc'+016AC

0128AC46 00EA7C1C 'CODE 0001 1B2E Main'+02F90

0128AC1A 00EC2896 'CODE 0011 1B2E Crypt'+00326

0128AB52 0127A668 'CODE 0036 1B2E Windows'+00348

0128AB18 01284934 'CODE 0007 1B2E Events'+01264

0128AAFC 00EA9412 'CODE 0001 1B2E Main'+04786

0128AA74 012843F8 'CODE 0007 1B2E Events'+00D28

0128AA32 012841FA 'CODE 0007 1B2E Events'+00B2A

0128AA0A 000C79A2 'scod BFAC 189C'+016DE

0128A9E6 000CBFFC 'scod BFAC 189C'+05D38

0128A9CE 0007F942 'scod BFB0 189C'+04322

Spot any likely candidates? How about the one named "Crypt" with a "Windows" routine called immediately after it? Thank you Retrospect developer!

4. List the code at that location. IL EC2896

+00326 00EC2896 JSR $3F4A(A5) | 4EAD 3F4A

+0032A 00EC289A MOVE.W D0,D7 | 3E00

+0032C 00EC289C CMPI.W #$A703,D7 | 0C47 A703

+00330 00EC28A0 LEA $0010(A7),A7 | 4FEF 0010

+00334 00EC28A4 BNE.S 'CODE 0011 1B.Crypt'+00396 ; 00EC2906 | 6660

5. Set a breakpoint after the call (JSR) returns. BR EC289A

6. Resume running the program. G

7. Type any password into the dialog and press OK.

8. MacsBug will halt the program at that point. Now, step through line by line to see where the code takes us. S (and press return to step through each line)

+00336 00EC28A6 *MOVE.L A4,-(A7) | 2F0C

+00338 00EC28A8 JSR strlen | 4EAD 4CC2

+0033C 00EC28AC ADDQ.L #$4,A7 | 588F

+0033E 00EC28AE MOVE.L D0,-(A7) | 2F00

+00340 00EC28B0 MOVE.L A4,-(A7) | 2F0C

+00342 00EC28B2 JSR HASHBLOC | 4EAD 02DA

+00346 00EC28B6 CMP.L $0004(A3),D0 | B0AB 0004

+0034A 00EC28BA ADDQ.W #$8,A7 | 504F

+0034C 00EC28BC BEQ.S 'CODE 0011 1B.Crypt'+00396 ; 00EC2906

Oooh. This looks promising. The string length is calculated and passed into a routine named HASHBLOC. Thank you Retrospect developer!

Then, the result is compared to a long, which is located 4 bytes into a structure pointed to by A3. If they're equal, good things happen.

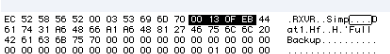

9. Before stepping into the CMP.L instruction, list the contents of A3. DM A3. It turns out this is the same as the data stored after the word 'Simp' (for SimpleEncrypt) in the data fork of the backup directory. (It is reasonable to store a hash of a password, as long as that it just for user verification and not the actual encryption key. Today, we would use a much longer hash and a salt.)

10. Now set D0 equal to the four bytes after the first four bytes of A3. D0=00130FEB (whatever it is for you)

11. Great. Now D0 equals the hash value for the comparison. Just run the program from here. G

Retrospect no longer showed the 'Wrong password' dialog and instead proceeded to ask me what I wanted to copy and to pick the destination. Hurray! The tape whirred. It stepped through each of the files, and 15 minutes later gave me a full list showing nothing was copied. Either I entered the wrong value, Retrospect uses the hash only for a quick check and needs the full password to perform the actual encryption, or it recomputes the hash at a later stage. In any case, this approach failed.

Brute Force

I decided to brute force the password with Basilisk II, as that runs at a much faster speed. So, I copied the HASHBLOC routine into Metrowerks, and then wrote a routine to step through all possible passwords. It outputs any password that produces a matching hash. With over 4 billion hash combinations, I figure not many random passwords will match. I'll either recognize or try each password it produces.

A Strong Password Is Always a Strong Password?

I was too tired that night to check my work before running the brute force routine. As I lay my head on my pillow, I chastized myself for not writing down the password or even a hint on the label. What password could I possibly have chosen that I thought I wouldn't need to write down? Then... after 33 years... I remembered.

The password is "Golden Slumbers".

That's 15 characters in length. It is estimated that it would take over a year to brute force an alpha-character-set password of that length. A dictionary-based attack would be much faster -- but I didn't code for that. Good thing I remembered my password.

Conclusion

Despite doing everything wrong (not documenting the equipment, backup software, or password), I recovered almost 1 GB of files without any corruption or issues. The old tape and drive worked flawlessly.

Looking through my files, I see I had System 6.0.7 with Maxima RAM disk and DayStar FastCache on one system drive. The other system drive has System 7.0.1 with Tune Up 1.1.1, Super Boomerang, and DiskDoubler. The development environment was Think C 5.0.1 and Think Reference 1.0. Communication was AOL 1.0 (really!) and AppleLink 6.1.

Good memories.

- David

Recently, while looking for something else in my old utilities collection, I ran into a folder containing Retrospect 1.3B, circa 1991/1992. That was enough to warrant trying to restore the tape. I ordered a Sony SDT-7000 in an external SCSI case from eBay, along with some new-old-stock tapes for practice.

I first used the practice tapes to determine that the tape drive was functioning and was not going to eat my backup. Then, after inserting my real backup tape, I was greeted with the following dialog:

Oh no! What password did I use 33 years ago?

After trying the usual passwords, I decided to crack the software. I've done this on many other programs from that era. Usually, they do a simple comparison against a plain-text stored copy of the password, or better ones compare it to a hash. Simply replacing the fail condition with a NOP or changing the success branch to an unconditional BRA is enough to crack the program. For example, this technique works with HDT drivers because they don't want to incur the speed penalty of encrypting/decrypting the hard drive sectors.

Here are the steps to take:

1. Make sure the debugger, MacsBug, is installed

2. On the password request screen, press the interrupt button on the Mac to drop into MacsBug.

3. Type SC6 to get a list of the routines on the stack. Usually, the last several will be in the operating system. You're looking for application routines, which are usually marked 'CODE xxxxx' because they come from the program's 'CODE' resource.

0128AD82 01275E50 'CODE 0009 1B2E Arc'+016AC

0128AC46 00EA7C1C 'CODE 0001 1B2E Main'+02F90

0128AC1A 00EC2896 'CODE 0011 1B2E Crypt'+00326

0128AB52 0127A668 'CODE 0036 1B2E Windows'+00348

0128AB18 01284934 'CODE 0007 1B2E Events'+01264

0128AAFC 00EA9412 'CODE 0001 1B2E Main'+04786

0128AA74 012843F8 'CODE 0007 1B2E Events'+00D28

0128AA32 012841FA 'CODE 0007 1B2E Events'+00B2A

0128AA0A 000C79A2 'scod BFAC 189C'+016DE

0128A9E6 000CBFFC 'scod BFAC 189C'+05D38

0128A9CE 0007F942 'scod BFB0 189C'+04322

Spot any likely candidates? How about the one named "Crypt" with a "Windows" routine called immediately after it? Thank you Retrospect developer!

4. List the code at that location. IL EC2896

+00326 00EC2896 JSR $3F4A(A5) | 4EAD 3F4A

+0032A 00EC289A MOVE.W D0,D7 | 3E00

+0032C 00EC289C CMPI.W #$A703,D7 | 0C47 A703

+00330 00EC28A0 LEA $0010(A7),A7 | 4FEF 0010

+00334 00EC28A4 BNE.S 'CODE 0011 1B.Crypt'+00396 ; 00EC2906 | 6660

5. Set a breakpoint after the call (JSR) returns. BR EC289A

6. Resume running the program. G

7. Type any password into the dialog and press OK.

8. MacsBug will halt the program at that point. Now, step through line by line to see where the code takes us. S (and press return to step through each line)

+00336 00EC28A6 *MOVE.L A4,-(A7) | 2F0C

+00338 00EC28A8 JSR strlen | 4EAD 4CC2

+0033C 00EC28AC ADDQ.L #$4,A7 | 588F

+0033E 00EC28AE MOVE.L D0,-(A7) | 2F00

+00340 00EC28B0 MOVE.L A4,-(A7) | 2F0C

+00342 00EC28B2 JSR HASHBLOC | 4EAD 02DA

+00346 00EC28B6 CMP.L $0004(A3),D0 | B0AB 0004

+0034A 00EC28BA ADDQ.W #$8,A7 | 504F

+0034C 00EC28BC BEQ.S 'CODE 0011 1B.Crypt'+00396 ; 00EC2906

Oooh. This looks promising. The string length is calculated and passed into a routine named HASHBLOC. Thank you Retrospect developer!

Then, the result is compared to a long, which is located 4 bytes into a structure pointed to by A3. If they're equal, good things happen.

9. Before stepping into the CMP.L instruction, list the contents of A3. DM A3. It turns out this is the same as the data stored after the word 'Simp' (for SimpleEncrypt) in the data fork of the backup directory. (It is reasonable to store a hash of a password, as long as that it just for user verification and not the actual encryption key. Today, we would use a much longer hash and a salt.)

10. Now set D0 equal to the four bytes after the first four bytes of A3. D0=00130FEB (whatever it is for you)

11. Great. Now D0 equals the hash value for the comparison. Just run the program from here. G

Retrospect no longer showed the 'Wrong password' dialog and instead proceeded to ask me what I wanted to copy and to pick the destination. Hurray! The tape whirred. It stepped through each of the files, and 15 minutes later gave me a full list showing nothing was copied. Either I entered the wrong value, Retrospect uses the hash only for a quick check and needs the full password to perform the actual encryption, or it recomputes the hash at a later stage. In any case, this approach failed.

Brute Force

I decided to brute force the password with Basilisk II, as that runs at a much faster speed. So, I copied the HASHBLOC routine into Metrowerks, and then wrote a routine to step through all possible passwords. It outputs any password that produces a matching hash. With over 4 billion hash combinations, I figure not many random passwords will match. I'll either recognize or try each password it produces.

A Strong Password Is Always a Strong Password?

I was too tired that night to check my work before running the brute force routine. As I lay my head on my pillow, I chastized myself for not writing down the password or even a hint on the label. What password could I possibly have chosen that I thought I wouldn't need to write down? Then... after 33 years... I remembered.

The password is "Golden Slumbers".

That's 15 characters in length. It is estimated that it would take over a year to brute force an alpha-character-set password of that length. A dictionary-based attack would be much faster -- but I didn't code for that. Good thing I remembered my password.

Conclusion

Despite doing everything wrong (not documenting the equipment, backup software, or password), I recovered almost 1 GB of files without any corruption or issues. The old tape and drive worked flawlessly.

Looking through my files, I see I had System 6.0.7 with Maxima RAM disk and DayStar FastCache on one system drive. The other system drive has System 7.0.1 with Tune Up 1.1.1, Super Boomerang, and DiskDoubler. The development environment was Think C 5.0.1 and Think Reference 1.0. Communication was AOL 1.0 (really!) and AppleLink 6.1.

Good memories.

- David